Introduction

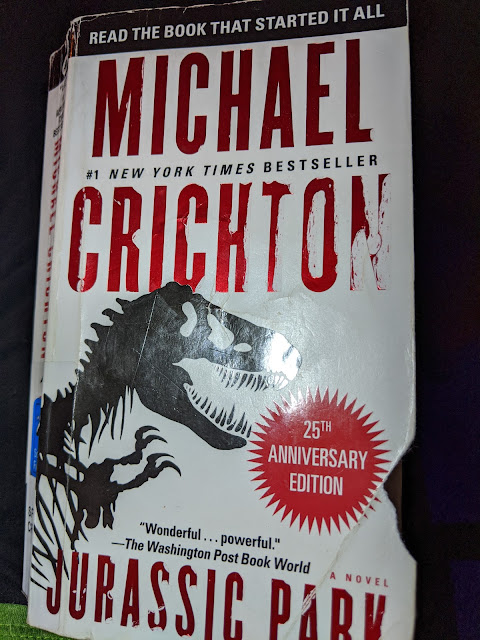

"The InGen Incident"

from Jurassic Park (the book),

by Michael Crichton

The late twentieth century has witnessed a scientific gold rush of astonishing proportions: the headlong and furious haste to commercialize genetic engineering. This enterprise has proceeded so rapidly-with so little outside commentary-that its dimensions and implications are hardly understood at all.

Biotechnology promises the greatest revolution in human history. By the end of this decade, it will have outdistanced atomic power and computers in its effect on our everyday lives. In the words of one observer, "Biotechnology is going to transform every aspect of human life: our medical care, our food, our health, our entertainment, our very bodies. Nothing will ever be the same again. It's literally going to change the face of the planet."

But the biotechnology revolution differs in three important respects from past scientific transformations.

First, it is broad-based. America entered the atomic age through the work of a single research institution, at Los Alamos. It entered the computer age through the efforts of about a dozen companies. But biotechnology research is now carried out in more than two thousand laboratories in America alone. Five hundred corporations spend five billion dollars a year on this technology.

Second, much of the research is thoughtless or frivolous. Efforts to engineer paler trout for better visibility in the stream, square trees for easier lumbering, and injectable scent cells so you'll always smell of your favorite perfume may seem like a joke, but they are not. Indeed, the fact that biotechnology can be applied to the industries traditionally subject to the vagaries of fashion, such as cosmetics and leisure activities, heightens concern about the whimsical use of this powerful new technology.

Third, the work is uncontrolled. No one supervises it. No federal laws regulate it. There is no coherent government policy, in America or anywhere else in the world. And because the products of biotechnology range from drugs to farm crops to artificial snow, an intelligent policy is difficult.

But most disturbing is the fact that no watchdogs are found among scientists themselves. It is remarkable that nearly every scientist in genetics research is also engaged in the commerce of biotechnology. There are no detached observers. Everybody has a stake.

Biotechnology promises the greatest revolution in human history. By the end of this decade, it will have outdistanced atomic power and computers in its effect on our everyday lives. In the words of one observer, "Biotechnology is going to transform every aspect of human life: our medical care, our food, our health, our entertainment, our very bodies. Nothing will ever be the same again. It's literally going to change the face of the planet."

But the biotechnology revolution differs in three important respects from past scientific transformations.

First, it is broad-based. America entered the atomic age through the work of a single research institution, at Los Alamos. It entered the computer age through the efforts of about a dozen companies. But biotechnology research is now carried out in more than two thousand laboratories in America alone. Five hundred corporations spend five billion dollars a year on this technology.

Second, much of the research is thoughtless or frivolous. Efforts to engineer paler trout for better visibility in the stream, square trees for easier lumbering, and injectable scent cells so you'll always smell of your favorite perfume may seem like a joke, but they are not. Indeed, the fact that biotechnology can be applied to the industries traditionally subject to the vagaries of fashion, such as cosmetics and leisure activities, heightens concern about the whimsical use of this powerful new technology.

Third, the work is uncontrolled. No one supervises it. No federal laws regulate it. There is no coherent government policy, in America or anywhere else in the world. And because the products of biotechnology range from drugs to farm crops to artificial snow, an intelligent policy is difficult.

But most disturbing is the fact that no watchdogs are found among scientists themselves. It is remarkable that nearly every scientist in genetics research is also engaged in the commerce of biotechnology. There are no detached observers. Everybody has a stake.

The commercialization of molecular biology is the most stunning ethical event in the history of science, and it has happened with astonishing speed. For four hundred years since Galileo, science has always proceeded as a free and open inquiry into the workings of nature. Scientists have always ignored national boundaries, holding themselves above the transitory concerns of politics and even wars. Scientists have always rebelled against secrecy in research, and have even frowned on the idea of patenting their discoveries, seeing themselves as working to the benefit of all mankind. And for many generations, the discoveries of scientists did indeed have a peculiarly selfless quality.

When, in 1953, two young researchers in England, James Watson and Francis Crick, deciphered the structure of DNA, their work was bailed as a triumph of the human spirit, of the centuries-old quest to understand the universe in a scientific way. It was confidently expected that their discovery would be selflessly extended to the greater benefit of mankind.

Yet that did not happen. Thirty years later, nearly all of Watson and Crick's scientific colleagues were engaged in another sort of enterprise entirely. Research in molecular genetics had become a vast, multibillion dollar commercial undertaking, and its origins can be traced not to 1953 but to April 1976.

That was the date of a now famous meeting, in which Robert Swanson, a venture capitalist, approached Herbert Boyer, a biochemist at the University of California. The two men agreed to found a commercial company to exploit Boyer's gene-splicing techniques. Their new company, Genentech, quickly became the largest and most successful of the genetic engineering start-ups.

Suddenly it seemed as if everyone wanted to become rich. New companies were announced almost weekly, and scientists flocked to exploit genetic research. By 1986, at least 362 scientists, including 64 in the National Academy, sat on the advisory boards of biotech firms. The number of those who held equity positions or consultancies was several times greater.

When, in 1953, two young researchers in England, James Watson and Francis Crick, deciphered the structure of DNA, their work was bailed as a triumph of the human spirit, of the centuries-old quest to understand the universe in a scientific way. It was confidently expected that their discovery would be selflessly extended to the greater benefit of mankind.

Yet that did not happen. Thirty years later, nearly all of Watson and Crick's scientific colleagues were engaged in another sort of enterprise entirely. Research in molecular genetics had become a vast, multibillion dollar commercial undertaking, and its origins can be traced not to 1953 but to April 1976.

That was the date of a now famous meeting, in which Robert Swanson, a venture capitalist, approached Herbert Boyer, a biochemist at the University of California. The two men agreed to found a commercial company to exploit Boyer's gene-splicing techniques. Their new company, Genentech, quickly became the largest and most successful of the genetic engineering start-ups.

Suddenly it seemed as if everyone wanted to become rich. New companies were announced almost weekly, and scientists flocked to exploit genetic research. By 1986, at least 362 scientists, including 64 in the National Academy, sat on the advisory boards of biotech firms. The number of those who held equity positions or consultancies was several times greater.

It is necessary to emphasize how significant this shift in attitude actually was. In the past, pure scientists took a snobbish view of business. They saw the pursuit of money as intellectually uninteresting, suited only to shopkeepers. And to do research for industry, even at the prestigious Bell or IBM labs, was only for those who couldn't get a university appointment. Thus the attitude of pure scientists was fundamentally critical toward the work of applied scientists, and to industry in general. Their long-standing antagonism kept university scientists free of contaminating industry ties, and whenever debate arose about technological matters, disinterested scientists were available to discuss the issues at the highest levels.

But that is no longer true. There are very few molecular biologists and very few research institutions without commercial affiliations. The old days are gone. Genetic research continues, at a more furious pace than ever. But it is done in secret, and in haste, and for profit.

But that is no longer true. There are very few molecular biologists and very few research institutions without commercial affiliations. The old days are gone. Genetic research continues, at a more furious pace than ever. But it is done in secret, and in haste, and for profit.

In this commercial climate, it is probably inevitable that a company as ambitious as International Genetic Technologies, Inc., of Palo Alto, would arise. It is equally unsurprising that the genetic crisis it created should go unreported. After all, InGen's research was conducted in secret; the actual incident occurred in the most remote region of Central America; and fewer than twenty people were there to witness it. Of those, only a handful survived.

Even at the end, when International Genetic Technologies filed for Chapter 11 protection in San Francisco Superior Court on October 5, 1989, the proceedings drew little press attention. It appeared so ordinary: InGen was the third small American bioengineering company to fail that year, and the seventh since 1986. Few court documents were made public, since the creditors were Japanese investment consortia, such as Hamaguri and Densaka, companies which traditionally shun publicity. To avoid unnecessary disclosure, Daniel Ross, of Cowan, Swain and Ross, counsel for InGen, also represented the Japanese investors. And the rather unusual petition of the vice consul of Costa Rica was heard behind closed doors. Thus it is not surprising that, within a month, the problems of InGen were quietly and amicably settled.

Parties to that settlement, including the distinguished scientific board of advisers, signed a nondisclosure agreement, and none will speak about what happened-but many of the principal figures in the "InGen incident" are not signatories, and were willing to discuss the remarkable events leading up to those final two days in August 1989 on a remote island off the west coast of Costa Rica.

Go

read

this

book!

No comments:

Post a Comment